Let the journey of self-discovery enrich your life...

According to Webster’s Dictionary, a lie is “an untrue statement with intent to deceive.” Obviously we all can relate to telling a lie. Whether it’s to make ourselves look better or cover up an embarrassing fact (or even to avoid hurting someone else’s feelings), I’d say with a high degree of confidence that no one has avoided telling a lie at one point or another in their lives.

These lies, however, are often transitory moments that do not define who we are and how we relate to others in general. Therefore, they don’t necessarily require much (if any) self-examination.

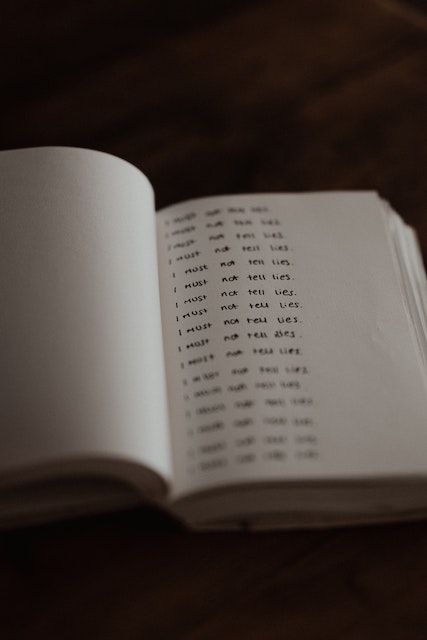

However, there are those who seem unable to go through their lives without consistent patterns of deceiving others. They’re often referred to as “pathological liars” or “compulsive liars.” These individuals often appear helpless in their inability to be truthful. . . with themselves and with others.

What follows is a chronic liar telling his story. Although it’s written by me, it’s informed by my years working with clients struggling with compulsive lying.

Jay’s story: Notes from a pathological liar

I was a young kid when it really hit me: it’s okay to make things up.

Maybe I was six or seven, in elementary school anyway, and one time the teacher brought in an author to speak to us. Not just any author, but the woman who wrote the book the class had loved, the one the teacher had been reading us during storytime for months.

I remember the teacher asking the writer how she came up with her ideas, and that struck me as very wrong. She didn’t “come up with” the story of the little girl who couldn’t find her socks and while hunting for them found a baby bird that had fallen out of its nest, she had lived that…she must’ve been that little girl once, searching for her missing socks in the tall grass.

You can’t just make things up, I told myself then. That’s lying!

Fiction versus real life: the line gets blurred

As I got older, I guess I blurred the line between lying and storytelling . . . by living it.

My mom had been in and out of mental health hospitals for much of my childhood, and my workaholic dad felt like a benign shadow more than a bonafide parent. So once I learned how to read, I lost myself in books, the stories within them more real to me — and more appealing — than my “reality” of unwell mom and barely-there dad.

I felt at home in the stories. I felt empowered. I felt less lonely. Even though they weren’t about me, I saw myself in them. I swapped every main character out for myself and lived within the pages.

And then the stories became a living tapestry for me, materials to cloak my life in. When my mother didn’t show up for parent-teacher conference and the teacher pulled me aside to ask about it the next day, the made-up scenario borrowed from the book I’d been reading felt natural: “My mom had to go to St. Louis, where the big arch is, to take care of her dad who got really sick. She had to rush off, she must’ve forgot to tell you.”

That was better than the truth, the only truth I knew at that point: that sometimes I could count on my mom to do mom things, and sometimes I couldn’t. The lies protected me from embarrassment, and from the pity of others, which made me feel all kinds of awful.

But let’s be clear: I am not blaming fiction for my fiancee giving up on me and ending our engagement. “I can’t take it anymore, Jay,” she said, angrily twisting the diamond solitaire I’d bought her till she wrenched it off her finger. “I can’t trust anything you say. I doubt you even know what’s the truth and what’s a lie anymore.”

The compulsive lying becomes a lifeline

Even that ring on her finger, the story I gave her behind it was a lie.

The truth? I’d put fifty bucks down and entered into a four-year payment plan. One I had to default on four months in because I lost my job. Because my boss found out about the lies on my resume. “Material” lies, he kept stressing. But that’s another story…

I told Sabrina I bought it with an inheritance from my (wealthy) grandfather. An inheritance I’d been holding onto for years, saving for something “truly special.” I led her to believe that my family “had means,” but I did it in such a way that implied I was sheepish and vaguely apologetic about growing up in such privilege when so many hadn’t. I was determined to work hard to balance things out. She seemed to like that.

The truth? I never even knew my grandfathers . . . one died before I was born — penniless — and I didn’t know the other one (not even his identity) because my mother never knew him, never knew who he was.

The lies I wove made Sabrina believe I could’ve used any of the many funds at my disposal to buy her diamond ring, but symbolically, I busted out that inheritance that meant so much to me. She even told her own parents the story when we visited them, and wow, I had thought booze and drugs were reality-shapers . . . they’re nothing compared to the high I got hearing someone else — someone who meant so much to me — repeating my lies. It caused my story to come alive in a powerful way, caused my lies to shift to truth before my eyes.

I realized I could never go back, could never risk her finding out the truth about my background. The story she’d bought, the one she was so proud of — the one that made up her perception of me — became my lifeline.

The house of cards built on deceit collapses

Sabrina really wanted to buy a house, and even though I tried to kick the can down the road, she wouldn’t be deterred, so we went through the process, my lies tougher to uphold in the cold hard light of numbers. And evidence. Pay stubs. Tax returns (themselves which were built on a hefty stack of lies).

My credit score was in the toilet, but I feigned shock. I claimed not to know anything about all the delinquent accounts, and so convincing was I, that Sabrina and the mortgage broker were sure I was the victim of identity theft, without me even needing to utter either of those words.

Even when she happened to notice that one of the accounts in collection was the jewelry store when I purchased the aforementioned engagement ring, I was able to (pretty easily) convince her that the identity thief obviously used an already-open account to steal from me, in addition to opening new ones.

And once she (unwittingly) accepted a lie, it was like it became an inextricable part of our history, woven into the fabric of us. We moved on, we moved past it.

But when the lies involved other people — people beyond my control — they weren’t so easy for me to protect and sustain.

Like the statement from the jewelry store getting misdirected to the apartment I’d moved into with Sabrina instead of the P.O. box I’d routed it to. Like her seeing it was her ring I was paying for. Like her calling the store and getting a pic of the contract sent to her, complete with my unmistakable signature.

Although I tried, and maybe it would’ve worked on someone other than Sabrina, I couldn’t talk my way out of that one.

Which made her doubt that I had money saved at all, which made her doubt that I’d lost my job for the reason I said I did, which made her doubt I’d even had the job I’d claimed to have. The whole intricate framework was collapsing before my eyes, and I was powerless to keep it standing.

And moment of truth: even if I knew it was going to play out the same way, with her walking out on me, the problem is, I wouldn’t have been able to stop myself from lying.

Simultaneous knowing and not-knowing

I remember living with my aunt and uncle for a few months when I was a kid, one of the times my mother “wasn’t well.” That was the extent of what they’d tell me then, that she “wasn’t well.”

Many years later I learned that I spent that summer with my aunt and uncle because my mother was in a psychiatric hospital after a serious suicide attempt. I remember feeling the tenseness in my aunt’s house, even though I was too young to conceptualize it as tenseness, remember tiptoeing to the top of the stairs when they thought I was in bed and eavesdropping on their conversations, knowing something was very wrong but not knowing what it was.

That irreconcilable knowing and not-knowing would keep me awake, and the only way I could get to sleep was sinking into stories, the ones in books and the ones I’d make up for myself, my fantasies of running away and being taken care of by a family that never spoke in tense whispers, where nobody “wasn’t well,” where the mom and dad were bright-eyed and eager to hear what I had to say, where we all held hands around the dinner table, even when Dad would have to disengage for a moment to pour me more milk.

Somewhere along the way I lost the thread of which details were “true” and which were “false.” Those words — true and false — didn’t even matter to me, so irrelevant were they to what I needed to survive. Rather, it was a matter of which things I’d tell others that would make me feel better, would protect me from further hurt.

My lies became my friends in a real way. I could turn to them whenever I was uncertain or lost in a world that often felt completely overwhelming. They made me feel special in ways that eluded me in my “real” relationships, and when one lie stopped working for me I could simply replace it with another, one that offered me the promise that I was better off than I really was.

I know all kids lie to an extent — maybe all people do — but my lies became the thing I could count on most. I didn’t lie occasionally or just when it suited me, I lied every time I was speaking . . . whether there was someone there to hear me or not, whether the words were spoken out loud or not.

Can you understand why that boy lied?

I’ve been in therapy awhile now, and though I still sometimes reach for lies in a knee-jerk way, the way someone else might reach for a drink or a cigarette, I’m now aware of times when I’m not lying. Sometimes those times feel surreal, sometimes they feel close to natural. But even the awareness of fact versus fiction, and that I have the choice about which to tell myself or others, is huge for me.

It took me awhile to even start being truthful with my therapist, if you can believe it. I mean, he’s someone who I’m pretty sure isn’t going to judge me, who I’m seeing because I’m chronically lying, and I was lying all the time. At some point I was struck by what a colossal waste that was, and I broke through my own impasse and started telling him the truth.

“Can you be kind to that boy you were?” he asked me once. “Can you understand him now, and acknowledge that the lying helped him make it through an incredibly painful childhood?”

I was so stunned to hear that, to consider it — and so relieved at the same time — that I cried and cried, maybe more than I ever had before in my life.

*** *** ***

In a follow-up article, we will explore in more detail how Jay’s childhood traumas set in motion his profound and pervasive need to hide, and how lying helped him achieve that hiding.

Rich Nicastro, PhD is a licensed clinical psychologist based in Austin, Texas. He has worked with individuals and couples for 25 years and has extensive experience working with trauma survivors and those who struggle with compulsive lying and secrecy. Dr. Nicastro offers teletherapy to clients throughout the United States. To determine if you’re in a state in which he is licensed, click here.

Pingback:The Inner World of a Compulsive Liar | Richard Nicastro, PhD