As a psychologist working with individuals as well as running therapy groups, one of the most powerful things I’ve witnessed over the years is the healing and growth people can experience when they connect with others who have experienced the same kind of pain. One of the most difficult aspects of grieving, outside of the ache of missing the person you love, is how alone it can make you feel. So hearing from others who are struggling along the same path can be the life jacket that keeps you afloat. Also, hearing that someone else was blindsided by a similar tragedy, and knowing that they survived it, can serve as a powerful type of inspiration, one that someone who hasn’t experienced that kind of loss can’t offer.

It is for those reasons that I’ll be posting articles from a guest blogger who lost her adult son in 2013. Laura had recently been telling a friend that she was finally ready to write about her grief and her journey from emotional fracturedness to feeling a familiar wholeness again, yet she didn’t want to do so in any kind of structure that would feel like pressure (a book, for instance). Also, because she was at a new job and in a new place, she said she didn’t want people who had newly met her to know about the details of her last few years. As she told me, “My grief is my own, and I want to decide with whom I’ll share it. Sometimes when people know you lost a child, they treat you differently, and I don’t want that.”

The friend she was talking about writing with is a colleague of mine, who knows about my blog. He suggested that she try writing pieces to share in this forum. She agreed, and liked the thought that maybe other bereaved individuals would find her posts and maybe get a tiny bit of comfort from them.

Grief, like love, is one of the most intensely personal things we humans will ever experience. There is not one “right” way to grieve, just as there is not one “right” way to love. So I’m not posting Laura’s articles to give you some type of roadmap for grieving. I’m offering them in the hopes that those of you who are grieving can gain a perspective on intense grief that only someone who has lived through it can give you. As with anything I publish on my websites, I encourage you to use what resonates for you and ignore the rest.

What follows is the first in a series of articles written by Laura. I want to thank Laura for her courage in sharing her story.

~~~

Grief: A Mother’s Journey

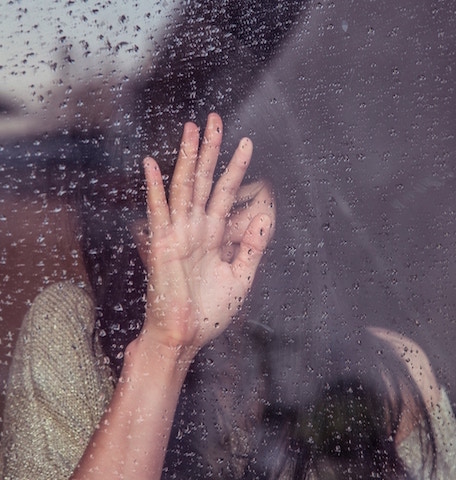

After my son died four-and-a-half years ago, I didn’t have the capacity to imagine that I would ever again care about helping anyone. Everything that had been normal and natural, everything that had felt familiar and reliable, everything that I believed had made me me was unreachable, squeezed outside of the tourniquet of grief. If anyone had dared tell me that someday I might try to articulate my pain and offer those words to other mourners, I would’ve hated them.

The only thing I could manage was breathing, and there were many moments where even that felt like beyond my ability.

One thing about grief is that it tricks the mind into believing this razing of everything in its path is fixed. It floods the brain with proclamations like Reprieves are a thing of the past and Don’t bother looking for a glimpse into the future, because it will be exactly like it is today. Only worse.

I’ve met many parents who have lost children, and I’ve met some who have said that we are not meant to have reprieves anymore. Reprieves or futures. That your children are meant to outlive you, and when they don’t, something in you is smashed beyond repair. And that’s the way it’s meant to be. I can say that I lost my mother when I was 15 and my father when I was 21, and the death of my son seared me with a brand of pain I had no idea existed.

I’ve met more bereaved parents, however, who have said that it’s not a matter of meant-to-bes, that surviving is within our reach — if we want it — and thriving is too.

Not without grieving, though. There’s no way to tidily circumvent or dissipate or banish the pain. There are illusions that make you think you can make an end-run around mourning your loss, but they reveal themselves to be illusions eventually.

As tempting as it is to anthropomorphize grief, to rewrite it as a villain with teeth and claws, kin to the Grim Reaper, skulking and scheming, it isn’t something outside of us. It can’t be. As much as we don’t want it, grief is a side effect of love. An inevitable corollary.

Intense grief can cut you off from everything and everyone, both psychically and literally. Maybe because it demands so much of us, resources we haven’t had to summon before. Maybe because we still don’t know we can survive it, so it distorts time in a particularly painful way. Maybe because it’s exhausting and terrifying, we’re sure no one has ever felt quite this way before.

So it’s not surprising that in that dark, cramped, airless place, I wouldn’t have had a thought for others.

And yet, now I do.

Before you assume that I am writing out of a place of sheer altruism, though, I need to say that it is not my only motivation for approaching Dr. Nicastro and asking if I could be a guest blogger. It’s true that I’d heard some truly painful things during the year after my son’s death (the most painful from well-intentioned people), but I also heard some truly helpful things, too. I do want to share those things in case they can help you (even if only because you can see glimpses of yourself in them and therefore have hope that someday you’ll care about others again), but also, I feel the need to write about my grief journey, maybe because I am a writer by trade.

Grief has a shape, I think (though maybe the shape is truly a temporary absence of shapes), and in writing about it, perhaps I’m adding my own shape now that I have walked through the fire and can imagine surviving (and maybe even thriving). I won’t say that my grief journey is “over” — it’s not a neat, linear, sequential thing. I will always, always miss my son. I will always, always wish he were still under the same sky.

But I can now look at pictures of him and have happy memories along with the ache of missing him. The sadness doesn’t unravel me when I remember him, the way it used to. The sadness is softer now, more gentle, more bearable. And it leaves room for me to live. To breathe without constriction (most of the time…I still have doubled-over moments of sharp emotional pain). To write. To think about you out there.

Thank you,

Laura